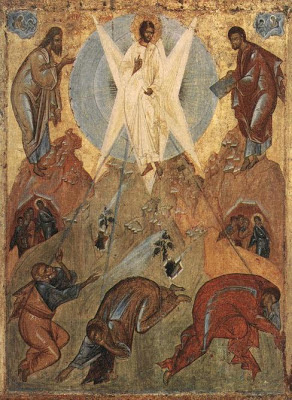

Here’s a verse from today’s Gospel reading (Luke 9.28-36):

Peter

and his companions were weighed down with sleep; but since they had stayed

awake, they saw his glory and the two men who stood with him.

It’s only St. Luke who tells us that when the

disciples went up a hill for the purpose of prayer, they were really too tired

to do the job. But while he is praying, Jesus is transfigured in their midst;

the appearance of his face changes and his clothes become dazzling white, and

Moses and Elijah appear to bear witness to the glory of God revealed in Christ.

The glory of God is a man

fully alive.

We need to go back to those words of St. Irenaeus

which I quoted: “The glory of God is a man fully alive.” That’s what we see in

Jesus - the Son of God, but at the same time fully human. The glory of his

Transfiguration is not something alien coming upon him. The Transfiguration of

Christ reveals the true glory, the real nature of a man who some want to write

off as “all too human.” Our humanity is a calling to share the glory of God.

Our weakness is something to be transfigured. God can use us because we are human.

Glory is not something to escape into from our

human condition. Glory is revealed because we are human with all the frailty

and frustrations of being what we are. But we wrestle with the frailty and

frustration. (Here) at St. Cuthbert’s this morning we can’t help but be

conscious of the loss we share by the death of Ian Severs on Friday evening. I

wonder what people who didn’t know Ian made of him when they first met him?

They’d find him in a wheelchair. With his Parkinson’s

the words didn’t always come out right, limbs didn’t always behave

properly; and he’d lost a leg - and had an arm that was barely functioning. You

needed to get to know Ian a bit to start to know the man - and to recognise

just how important he’s been, not only to the members of his family, not only to

his friends, but to us as a church, and more widely in showing what it is to be

fully alive even in the most extreme conditions of physical weakness and

disability. He was with us (here) in church at the Eucharist last Sunday. In

the conversations I had with him during the last week he didn’t say that he’d

been feeling unwell; he did say he’d

had a positive outcome from his last hospital check-up - but mainly he was

taken up with tackling problems of fabric we’re having at present in the church

and the hall. Problems they are to us - but Ian’s approach was to sort them

out.

Today our Diocese of Durham is encouraging us to

observe as “Giving Sunday.” It’s up to the parishes as to what they do with the

occasion - and it’s not the best time of year, I think, to be trying a

stewardship drive… to encourage people to put more money on the plate, or think

about increasing their standing order

for the church, or review the Gift Aids they might use to make their giving

more tax efficient. Of course we’d be delighted if you do all these things. But perhaps we need first to think of life as

a gift - in all that we receive from God, in the extent of God’s mercy, in the

generosity to which we are called as Christians to respond, in what we can give

back. It’s a time to express gratitude. I and the Church Council need to say thank you to all of you who give to

support the work of our church. I don’t need to say how much you should give. I realise that some people

get concerned about what they can

give. What I’d say now is that our giving is about recognising the gift we have

already received. As to the extent of our giving, it’s a strange thing but

people who are generous somehow find themselves able to go on being more and

more generous. Love itself does not count the cost.

I’m pretty hopeless at thinking of how to conduct

so-called “stewardship campaigns” to stimulate giving to the church - I’m not

starting a campaign now. But when we’ve had them in the past (at St.

Cuthbert’s), I’ve been glad for people who have been practical about what we

needed to do and who were ready to take a lead. One of those people was Ian

Severs. It was Ian who was ready to get

up in front of other people and tell them what we needed to be doing. He put

into practice what we needed as an example. He was down to earth.

And that’s when we see that the “glory of God” is

not something unworldly. It’s worked out in the here and now, within the limits

of our human capability, but at the same time able to be transformed - transfigured.

For all we have received - in terms of wealth,

health (and our weaknesses), material resources, and above all people who show us his grace at work, in

whom his glory is revealed, thanks be to God!